Memo #9: The Structure of our Society

John Rawls vs. Robert Nozick and my formulation of long-term utility maximization

Hi there,

I’m sure you missed my daily ramblings as I went on a short hiatus the past couple of days. By the end of this memo, you’ll see why I had to take a few days to collect and develop my thoughts.

Let’s dive right in.

Today, I’d like to dive into one of the most fundamental yet deeply contested questions in all of philosophy – how should we structure our society?

All the way from Socrates to the most influential of 20th-century philosophers, the giants of the field have spent better parts of their lives piecing together their answers to this very question.

In our modern world, this question often maps well onto a similar question - what is The State for? What goals should the government pursue vs. what should be left to private enterprises?

But first, a more fundamental question.

Why do we need The State?

Today, we take for granted the existence of The State. But, it isn’t obvious why we need one in the first place.

Think about it this way – if you're taxed at a 30% rate, then you are spending a third of your working hours laboring away for The State. The State that is probably wasting half of it, and allocating the rest toward whatever their vision of a good society happens to be during that election cycle. And guess what? You don’t get to opt-out. If you try, men in black suits show up at your door and throw you into prison.

So, why do we need The State?

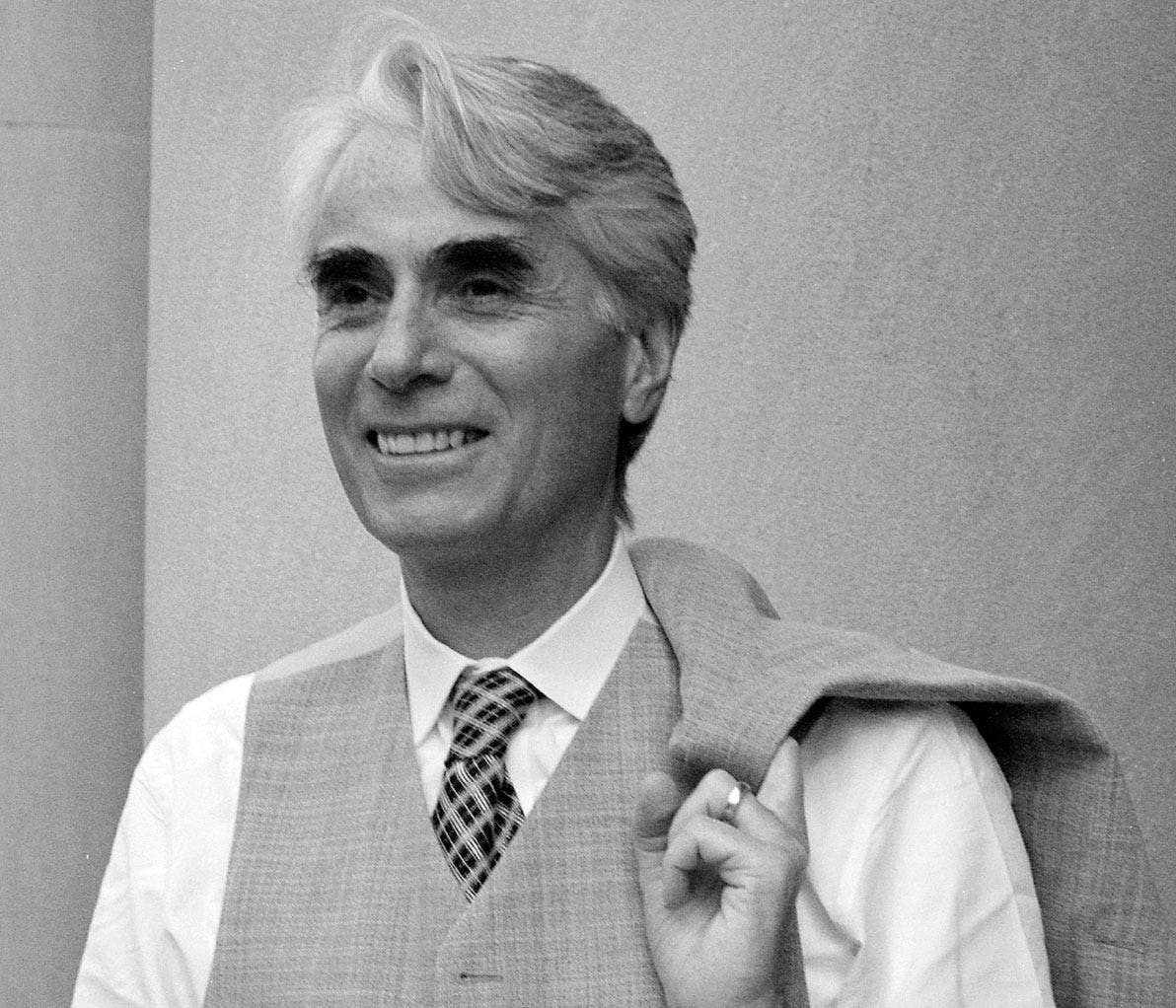

Enter Robert Nozick’s landmark text Anarchy, State, and Utopia (ASU, 1974). In this book, Nozick lays out a convincing case for why The State is required.

He asks us to consider the pre-political, pre-contractual humans living in nature. Completely left to their own devices, these humans would still want, say, security and protection. Inevitably, private bodyguard services will emerge. Since these bodyguards can’t reliably take on private clients and enforce rules in real-time, there will eventually be collisions between these bodyguards, leading to a whole lot of mess.

Nozick argues that if you carry out this scenario to its ultimate conclusion, what you get is an institution that protects life and enforces contracts under some set of universally agreed-upon laws. Lo and behold, The State is born.

What should the State do?

Once The State is born, the natural question we must ask is – what should this State do?

In this memo, I’d like to first present John Rawl’s Theory of Justice. Next, we will see how Nozick presents his theory of The Minimal State as a direct counter to Rawls. Finally, I’d like to lay out my personal perspective on how to think about the structure of societies from more of a systems-engineering lens.

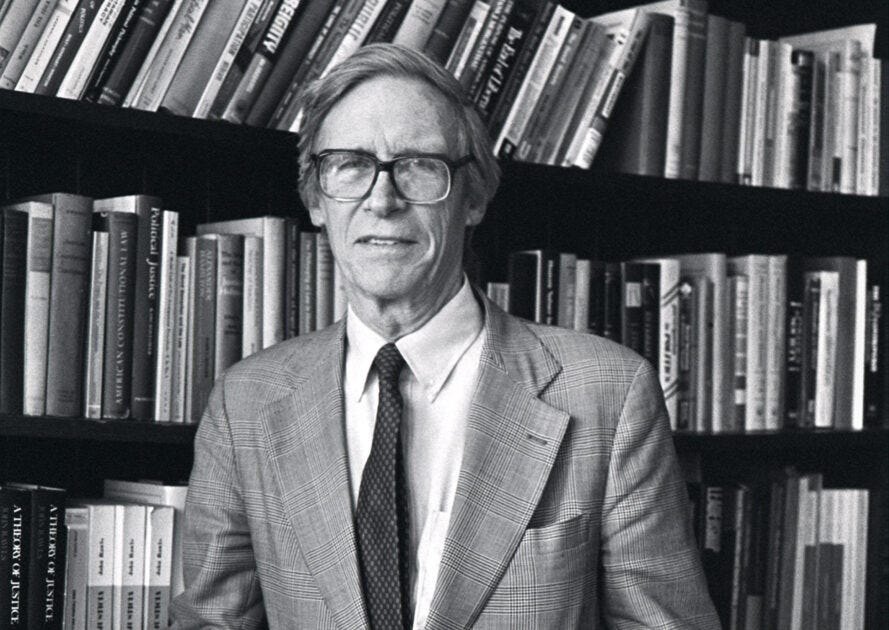

John Rawls: Theory of Distributive Justice

To Rawls, Justice is the primary substrate that society is made of. He writes,

Justice...is the first virtue of social institutions, as truth is to systems of thought.

Rawls defines justice to be broader in scope than, say, criminal justice. To him, to be just is to be fair. Justice is fairness.

It follows that for our social institutions to be just, they must ensure fairness amongst their citizens. He argues that because humans band together in a society that allows us to create a lot of surplus value than what we would working by ourselves, this value must be distributed fairly amongst the citizens of that society. This is what Rawls calls distributive justice.

Despite having redistributionist tendencies, John Rawls is not a socialist. Socialists are egalitarians. Under socialism, the primary goal is to make everyone equal, even if that means making everyone equally miserable.

On the contrary, Rawls recognizes that inequalities are neither avoidable nor always unjustified. He asks, what type of inequality is just, what makes these inequalities just, and what criteria do we use to determine that?

There are two important principles from Rawls’ work to understand his criteria to determine just vs. unjust inequalities

The maxi-min principle – that is, we should structure our society such that it maximizes the welfare of those at the minimum level of society.

The difference principle – that we should remove inequalities within society as much as we can until the removal of further inequalities would cause harm to the least advantaged.

Here is what Rawls is ultimately doing with his philosophical treatise on State and its role of ensuring justice – providing a philosophical justification for a modern progressive income tax.

Robert Nozick: The Minimal State

Nozick begins his formulation of The State from a completely different angle – he emphasizes rights, not justice. He famously starts with this sentence in his Anarchy, State, and Utopia –

Individuals have rights, and there are things no person or group may do to them (without violating their rights)

– (Nozick, 1974)

When individual rights are paramount, it follows that you can not sidestep those rights no matter how great the social benefit. For example, even if taking $100 from X to give to Y will produce $1000 worth of utility for Y (therefore the total sum of utilities being much greater), neither Y nor The State is allowed to coerce X into doing so, as doing that would inevitably violate X’s individual rights.

Nozick lands a deadly blow against one of Rawls’ core principles. Nozick argues that the maxi-min principle is not a consequence of human nature or Just societies, but a clutch for Rawls which he needs for the rest of his theory to work. When you really look at what humans want from their societies, it is not that we want to maxi-min the payoff matrix, but rather, we want basic enforcement of life, liberty, rights, and contracts.

To Nozick, these are the preconditions for a good society, and the scope of the government should not be mindlessly expanded beyond these duties.

Ultimately, Nozick is putting forward the notion of The Minimal State. A government that is not a paternalistic figure telling us how to live our lives and what choices we should be making, but one that protects rights and enforces contracts, allowing for private enterprises to freely operate and take care of the rest.

Working theory: Long term Utility Maximization

As many of you know, my background is in technical areas like CS and Math. In reading political philosophy, I’m realizing that many of the best philosophers are actually making technical systems-engineering type arguments, though they often resort to rhetoric, not equations.

So allow me to present a slightly different angle through which we can derive Nozick’s Minimal State.

First, consider that Utilitarianism, that is the social doctrine of maximizing the sum-total of all utility across society, is directly at odds with Nozick’s Minimal State. As we saw earlier, Nozick argues that individual rights are inviolable and neither a person nor a group (such as the government) may do anything to the individual harming her rights, no matter how great the benefit.

That said, we do want something like Utilitarianism. Clearly, states of the world with higher total utility are preferable than those with lower utility, albeit with some additional constraints.

Here’s why my working theory on not only how to rescue utilitarianism, but also go a step further and derive Nozick’s Minimal State from it.

Consider a simple mathematical formulation of utilitarianism

1. max U(S) at time t=T We’ve already seen how the simple utilitarian principle of maximizing the total utility (U) across Society (S) fails.

Maybe we can add another constraint – that we must preserve the individual rights of each member of that society.

2. max U(S) | subject to (preserve individual rights of s1, s2, ... s_n)

Adding this constraint gets us much farther into making utilitarianism more practical.

Such constraint optimization problems often have what are called dual equations – a different formulation that leads to the same solution as that of the original equations.

Here’s what I think the dual of the equation (2) is

3. max ∫ U(S) from t=T through t=∞

You can see why I call this Long-term Utility Maximization. Instead of maximizing utility across society at a fixed time T, we are now maximizing it both across society (space) and time t=T through infinity ∞.

This is still a work-in-progress, but here’s my central claim – while SPACE maximization of societal utility leads to Rawls’ version of the Just State, SPACE-TIME maximization of societal utility leads to Nozick’s Minimal State.

Here’s why – the SPACE only formulation of utilitarianism (eqn. 1) is a zero-sum redistributive variant of society. All you are really doing is taking utils from X and distributing to Y, who values those utils at a higher value than X. As an example, you are taking $100 from a first-world earner, who will barely notice it, and giving it to a kid in Africa who would use that amount to eat food for weeks.

However, in the SPACE-TIME formulation, you maximize utility not just across space, but across time as well. What this implies is that you can’t keep taking from X to give to Y because eventually, you hit an upper bound of total utility you can achieve. You hit the local maximum, but not the global one.

Given the TIME dimension, you can now start producing more utility, therefore making this a non-zero-sum domain. This means you are not limited to taking from X to give to Y, and instead have to think about what structure of society then leads to the greatest utility across space and time. The dual equation suggests that it’s the version where the individual rights constraints are satisfied, and people are at liberty to try out many experiments and get rewarded for their ingenuity and labor.

Ultimately, this framework gives us something resembling Nozick’s Minimal State + free-markets that maximize societal utility across both SPACE and TIME.

I’ll leave you with that formulation and encourage you to think more about it. Would love to hear your feedback so feel free to email if this interests you.

See you tomorrow,

Ayush